Stomas save lives and free people from fear and terrible discomfort. There is almost nothing someone cannot achieve with a happy, healthy stoma. However, they do take some work to manage and can be affected by a number of problems.1

If there is a common theme to these problems, it is that if they are spotted, they can almost always be sorted. It is worth knowing how to prevent problems occurring, as well as how best to respond if they do.

This guide deals with issues that affect the stoma itself. Problems to do with the pouch are covered in Issue 2 of Stoma Tips, and conditions affecting the skin will be dealt with in a future issue.

Troubleshooting your pouch

Issues covered in Part 1 of this series

- Leaks

- Odour

- Ballooning

- Pancaking

- Watery output

- Allergies

Bleeding

My stoma is bleeding!

Occasionally, a stoma might bleed, especially if it is being cleaned or has rubbed against its pouch. This is perfectly normal, and a little blood from the edge of a stoma appearing on a cleaning tissue is nothing to worry about. This is because the bowel that makes up your stoma contains lots of blood vessels, and these can bleed when pressed, much like your gums do when brushing your teeth.

However, if bleeding is persistent and doesn’t stop after 5–10 minutes, you should apply pressure to the area and contact your stoma nurse. This might take a little longer if you are on blood thinner or aspirin, as these make people bleed more easily. If you are speaking to a nurse, make sure to mention any medications you have recently taken, as they can arrange tests to see if the drugs might be the cause. Likewise, if the bleeding appears to be coming from further inside your bowel, or if you find blood in your stools, it is important to contact a healthcare professional who can check whether these are signs of something else. In the rare cases of serious bleeding, clinicians have a variety of ways to stop it, including direct pressure, cauterisation, sutures and silver nitrate.

Granulomas

My stoma is lumpy!

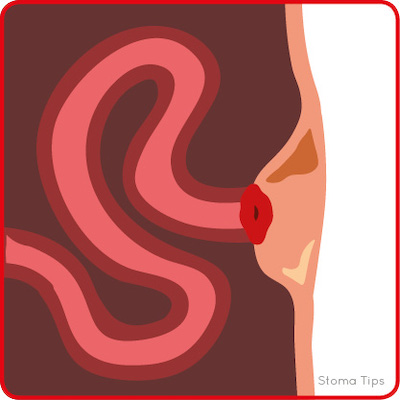

Granulomas are red lumps that form around the edge of a stoma. They are not normally painful, but they can bleed or cause mild irritation. Granulomas are part of the body’s natural protective response to potential infection or friction, and they tend to appear where the body is in frequent contact with abrasive or irritating substances.2

The best way to prevent granulomas from occurring is to make sure the pouch aperture is just the right size. It needs to fit closely enough to stop the contents reaching the skin, without being so tight it rubs against the stoma. The skin can also be protected using barrier accessories, including powders, sprays and rings.

If you have granulomas, a stoma nurse can help you get rid of them, perhaps by shrinking them with silver nitrate, and then make sure they don’t come back.

Stenosis

My stoma is too narrow!

The opening at the end of a stoma needs to be wide enough to let the contents out into the pouch. Very occasionally, this opening can become too narrow, making it more difficult to pass the contents, referred to as stenosis. This may cause abdominal cramps, increased wind and obstructed or explosive output.

Stenosis is sometimes a by-product of other stoma-related issues, such as ischaemia, retraction or scarring, and is most likely to occur soon after surgery. It can also result from changes to the bowel caused by pre-surgery radiation or other illness, especially Crohn’s disease.

If your stoma is having trouble passing, your stoma nurse will be able to check for stenosis and find a solution. The opening can be widened with a plastic tube, known as catheter dilation. The output itself can be made easier to pass by eating low-residue foods, drinking more fluids and taking stool softeners or laxatives. If these don’t resolve the problem, you may need surgery to refashion the stoma.

Adhesions

The body’s internal organs are naturally held in place with bands of scar-like connective tissue called adhesions. Should an organ be disrupted by surgery or other trauma, new adhesions will typically form around it. After the operation to create a stoma, most people (over 90%) will develop new adhesions around their bowel within days after surgery. These help hold the bowel in place and are generally harmless, with most people unlikely to ever be aware of their presence.3

However, adhesions can sometimes grow in a way that constricts part of the bowel, making it harder for food, fluids and gas to move through, and potentially causing persistent abdominal pain. These problems may not become apparent for months or even years after the initial surgery. Should adhesions cause discomfort or other problems, a stoma nurse will be able to help find a solution. Pain-relief is the preferred option, as further surgery may cause more adhesions.

Obstruction

My stoma is blocked!

As a stoma’s job is to let food and/or fluids out of your body, anything that gets in the way of that process is a problem, whether a partial blockage or a complete obstruction. These problems are uncommon but need to be resolved right away. A partial blockage in the bowel can make the output watery and unpleasant smelling and cause abdominal swelling and discomfort, as well as swelling of the stoma itself. A complete obstruction will stop a stoma’s output completely and cause severe abdominal cramping and swelling, often accompanied by nausea and/or vomiting.

A blockage can be caused by large pieces of food that have not been properly digested. You can ensure this doesn’t happen by being careful with how and what you eat, making sure to peel fruit and considering avoiding nuts, popcorn and coleslaw. However, blockages can also be the result of the bowel becoming narrowed or twisted, possibly related to the growth of adhesions (see box).

If you experience a blockage, whether partial or full, stop eating solid food until it is resolved and increase your fluid intake. Massaging your abdomen and taking a hot bath can help any blocked food to pass by itself. If the food will not pass and you start vomiting or the pain becomes severe, get to a hospital emergency department as soon as you can. The emergency team should be able to assess the extent of the blockage and attempt to resolve it. You may be given intravenous fluids to keep you hydrated, and potentially a nasogastric tube, which goes from your nose to your stomach, to drain fluids. If these methods don’t clear the obstruction, it may have to be done surgically.

Retraction

My stoma is too short!

Ideally, a stoma should spout a couple of centimetres from the surrounding skin, as this allows it to drop its contents right into the pouch. Sometimes a stoma will retract back into the skin, causing it to either lie flush (level) with the skin or sit within a dip below this level. This could be the result of issues with stoma formation, restricted blood flow or tension on the bowel, as well as weight gain or other changes in the surrounding skin.

A retracted stoma may have trouble emptying into the pouch. Its contents can become stuck around the stoma entrance, causing issues with the surrounding skin and making it harder for the pouch to form a secure seal and avoid leaks. A stoma nurse should be able to help address the causes of retraction and provide the right equipment to resolve these difficulties. This is likely to include convex pouches, which are shaped to gently push into the peristomal skin so that the stoma forms a spout. Modern convex pouches use softer materials that are especially effective. The seal may need to be built up with accessories, such as pastes, washers and flange-extenders, and the skin can be protected while it heals with a variety of wipes, sprays and powders.

A retracted or flush stoma takes a bit of extra care, but the right approach can get it under control. Guidance and support from a nurse are essential to choosing the right products, and deep convexity needs regular review to make sure the extra pressure isn’t doing any damage.

Prolapse

My stoma is too long!

A stoma should protrude only a few centimetres from the body. However, sometimes a stoma will begin to protrude further than is ideal, referred to as a prolapse. A prolapsed stoma should continue to work as normal, and, so long as it maintains its normal colour, is not a cause for alarm or immediate surgery. The main concerns are cosmetic. However, a prolapsed stoma can get in the way and make it harder to attach a stoma pouch. Stoma nurses are able to recommend the best kit and technique to make pouch changes as easy and effective as possible.

Prolapses generally occur in colostomies, especially loop colostomies in the transverse colon. A prolapse occurs when the stomach muscles that hold the organs in place are not strong enough to resist the pressure pushing on them from within the body. Stomach muscles can get weaker due to abdominal surgery, a lack of exercise or other health problems; meanwhile obesity, heavy coughing or serious constipation can put extra pressure on the bowel. Watching out for any of these issues and taking extra precautions is the best way to minimise the risk of a prolapse.

Wearing a stoma cap or shield will protect it from being squeezed or bashed when leaning or sitting. It is helpful to pick outfits that do not catch or drag the stoma, and loose-fitting items or pleated clothes can help conceal any bulges. Supportive garments are especially useful, either as a preventative measure or after a prolapse has occurred, as they can both support the stomach muscles and hold a prolapsed stoma in place.

A prolapse may come in and out of the body depending on your position and activity, often appearing smaller (or disappearing entirely) when lying down and getting longer throughout a busy, active day. Therefore, the pouch system needs to be able to accommodate the stoma’s changing size. Accessories such as barrier rings can help support a wider hole, while you can prevent a prolapse rubbing against the edge when it moves by using a mouldable flange, a one-piece pouch or a two-piece pouch with a low profile.

If you have a prolapsed stoma and you notice it changes in colour (darker or paler) or temperature or doesn’t seem to function properly, you should contact a health professional. They will help you decide whether it needs to be surgically repaired, in a process called revision.

Parastomal hernia

There’s a bulge by my stoma!

A parastomal hernia is a bulge under the skin next to a stoma, caused by a loop of bowel being pushed through the gap in the stomach muscles made to let the stoma through. A hernia is rarely painful, but it can cause a dragging sensation. The bulge and the stoma may appear to change in shape or size as you change position, and this uneven, changing surface can make it more difficult to form an effective seal for a pouch.

Hernias are one of the most common complications ostomates have to watch out for, and they can occur at any stage, whether weeks or years, after surgery. Abdominal surgery will always weaken the stomach muscles, so to stop a hernia from occurring or growing larger, these muscles need to be strengthened, supported and protected from unnecessary strain. Stomach muscles can be supported with special belts and garments, covered in Stoma Tips Issue 1, and strengthened with a series of light abdominal exercises, such as those detailed in Stoma Tips Issue 2. To reduce the strain that can cause or increase a hernia, it is advisable to avoid heavy lifting or very strenuous exercising, as well as to eat a balanced diet, stay a healthy weight and avoid smoking.

If a hernia does develop or get worse, contact a stoma nurse. They will be able to review it and recommend management options that make sure it doesn’t get bigger or get in the way of pouch adhesion. Surgical repair is possible, but it does not always work, and it is usually only recommended if the hernia causes an obstruction. Prevention is always best, but a hernia can be comfortably managed.

Ischaemia

My stoma is discoloured!

A healthy stoma needs a supply of fresh blood. Occasionally, something interrupts this blood flow, referred to as ischaemia. This causes the stoma to become swollen and discoloured, a process known as necrosis. Although up to a fifth of new stomas can have problems with blood flow, especially for people who are very overweight or very ill, it tends to only occur in the first 24 hours after surgery, when the nurse or surgical team should be able to spot it and respond promptly.

Ischaemia can be recognised by a change of colour, as the stoma becomes blueish, purplish or dark red, before turning black or dark brown with necrosis. This can be in spots or all around the stoma. An ischaemic stoma may also feel floppy or hard and dry, and it may show signs of swelling. However, it is important to remember that a healthy new stoma is usually a little larger for a few days after surgery before it shrinks back down again. Ischaemia, if left untreated, can develop an unpleasant smell.

Ischaemia is usually the result of an issue with how the stoma was made or the shape of the body wall putting pressure on the bowel. The hospital team should be able to work out the cause and resolve it. The team will then check if there is any necrosis and, if so, how far it has gone into the stoma. Usually, the stoma can be left to heal by itself, but, if there is deep necrosis, it might need to be refashioned. While recovering from surgery, wearing a transparent pouch will allow the team to keep an eye on your stoma, and a two-piece pouch will permit a closer look without having to do a full change.

References

2 Canadian Society of Intestinal Resarch. Bowel blockage or obstruction. 2019

Conclusion

Few of these problems are particularly common, and they can generally be either avoided or effectively sorted. Supporting and strengthening the stoma muscles is the best way to minimise the risk or extent of some of the most common problems, especially a parastomal hernia. Meanwhile, as you learn to perfect your pouching routine, your stoma will be healthier, as well as easier and faster to manage.

If a problem does occur, remember that you are not alone. There are nurses and doctors with the knowledge and experience to help you out, as well as plenty of peers who have been through the same issues and may be able to provide advice and support.

Sinéad Kelly O’Flynn is a Clinical Research Nurse, based in Cork, Ireland

Sinéad Kelly O’Flynn is a Clinical Research Nurse, based in Cork, Ireland

sineadkoflynn@gmail.com

The contents of this page are property of MA Healthcare and should not be reused without permission